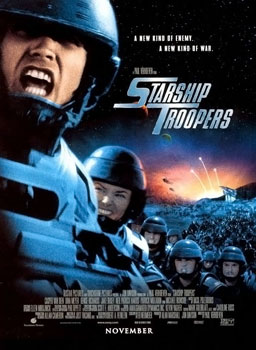

Great special effects do not a great movie make

The more you understand your enemy, the more you come to love him

The usual alien‑invasion metaphor from insecure and unconfident Whites for the decline of their culture, the War on Terror & the increased migration of those whom Whites consider inferior. Such aliens always seem to outnumber Whites, but the superior White intellect somehow manages to win the day - regardless of whether any war was necessary or not.

Here, the war of the aptly‑named Hegemon against the Formics is a thinly‑disguised attack on the behaviors of all those who are foreign to Whites - who Whites somehow imagine will change their culture for the worst. This results in Whites acting‑out (ie, becoming even more White), in a vain bid to fend‑off the cultural challenges Whites will always face from their static and uncompromising culture.

That this new enemy is presented as ants, to be squashed underfoot, references the White solidarity inherent in Institutional Racism; being denied here by the politically‑correct casting of many ethnicities - albeit in less than stellar roles. This movie is, after all, a justification for Western expansionism (& resulting genocide) in a story of what are, effectively, Hitler Youth trainees.

Whites will somehow save the Earth by only doing more of what they usually do: Dehumanizing their children into warlike robots. White survival is presented as being as paramount as it is without true purpose - other than mere survival or ancestor worship - since no White cultural values are expressed here that are worth preserving. This explains the bizarre White belief that one great war can bring about the end of all war! Not very likely given the inappropriately‑aggressive nature of Caucasians throughout their history and their obvious need of war and the vainglory that goes with it.

The more interesting aspect to this predictably morally‑confused movie is that of the revenge of the nerds. Clever White people are shown as being the true saviors here, despite the fact that human history offers few examples of such. In reality, bullying is the underlying theme here - along with the fear of fighting‑back inherent in trying to out‑think the bully; leaving no real dramatic exploration of the resulting tension between individualism and the need for teamwork.

By trying to create an indispensable leader, Whites sows the seeds of their own destruction, since the central focus then fatally shifts from defeating the enemy, to protecting the leader. The central absurdity here is that there is felt to be a need to copy the strategy of the enemy, even though this same strategy led to their defeat in a previous battle; namely, a single leader, with a host of followers, who can easily be defeated by killing the leader. This would require extensive security precautions to guard the leader’s life, which are not shown here and, in any case, would inhibit his room for maneuver. Here, the White man’s need for strong, dominant alpha‑male leaders (eg, Adolf Hitler) is at its most most apparent - and its most abjectly‑pathetic.

But terrorists cannot be defeated in this way because they usually operate in cells independent of one another; killing a terrorist leader will rarely lead to a collapse of their terrorist network. Thus, despite fighting ants here, it is Whites who appear the most ant‑like.

In real life, it is Whites who prize mediocrity over elitism. They prefer the complacency, laziness & moral turpitude engendered by White supremacy, over working hard for a living - work they prefer People of Color to perform.

Leaders are born (not made) and no conflation of the Personal with the Political - as depicted here in calls for privacy to be sacrificed for the so‑called greater good - will ever change that. Would humans really come together to defeat a common enemy, when history shows otherwise? Where are the enemy collaborators and the pacifists, aiding the enemy, in this shallow drama?

The psycho‑politics here reflects the militaristic power fantasies inherent in science‑fiction’s most basic narrative structures. Without irony, this movie would find an easy place on the American Nazi Party’s recommended list - as would Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces - from which it derives its mythological inspiration - but quite unlike Alfred Bester subverting the inherent assumptions of such a plot with The Stars My Destination.

The characterization is limited in this movie since there is no convincing explanation as to why the main character experiences grief at killing (& eventual love for his enemy); nor why the Formics would wish to communicate with him and, apparently, no‑one else; nor why the enemy regrets their original attack on Earth - never intending to continue the war while being capable of a masochistic kind of forgiveness.

Here we see a good example of the fact that Whites - albeit in a dim light - understand that they possess a superficial and rigidly‑hierarchical culture which offers little protection from external threats, since the destruction of its core will automatically lead to the destruction of its constituent parts. That such a fragile culture can so easily be destroyed in this confusing paean to identity, human sacrifice (soldiers as pawns) & understanding/love is strong testament to the power‑mad delusions underlying it.